Celebrating Lucille Hunter and Her Legacy of Badassery

by Aneke Mendarozequeta

Since moving to Dawson I have been regaled with tales of explorers and adventurers, striking stories of strength and perseverance against all odds. Yukon’s history is full of kooky and colourful characters, and I can think of no one who better exemplifies this trailblazing spirit than Lucille Hunter. Lucille was one of the first black women to arrive in the Klondike and the only one documented to have been both a prospector and a miner during the Gold Rush.

National Film Board photographer Roloff Beny captured this charming image of Lucile in her 80s at the Whitehorse shipyards, ca 1964. Courtesy of Hidden Histories Society Yukon.

Lucille and her husband Charles jumped at the chance to seize a bright future for themselves upon hearing tales of gold in the far north. So in the autumn of 1897 at the meager age of 19, and pregnant, Lucille loaded her life into a few travelling bags and set out for that rugged land with her husband in tow. Leaving Michigan, the pair headed for the west coast, landing tickets on a steamer that would see them to the lawless town of Wrangell. From there the two decided on the Stikine Trail, a harrowing journey that would take them farther inland than the more popular Skagway entrance and Chilkoot Pass. This interior route crept through the thick forests of Northern British Columbia to Teslin Lake, the pair had chosen this journey believing the passage to be cheaper, easier, and faster. Unfortunately it was not. Indeed, this route was more arduous, more perilous, and required immense physical and psychological fortitude to execute.

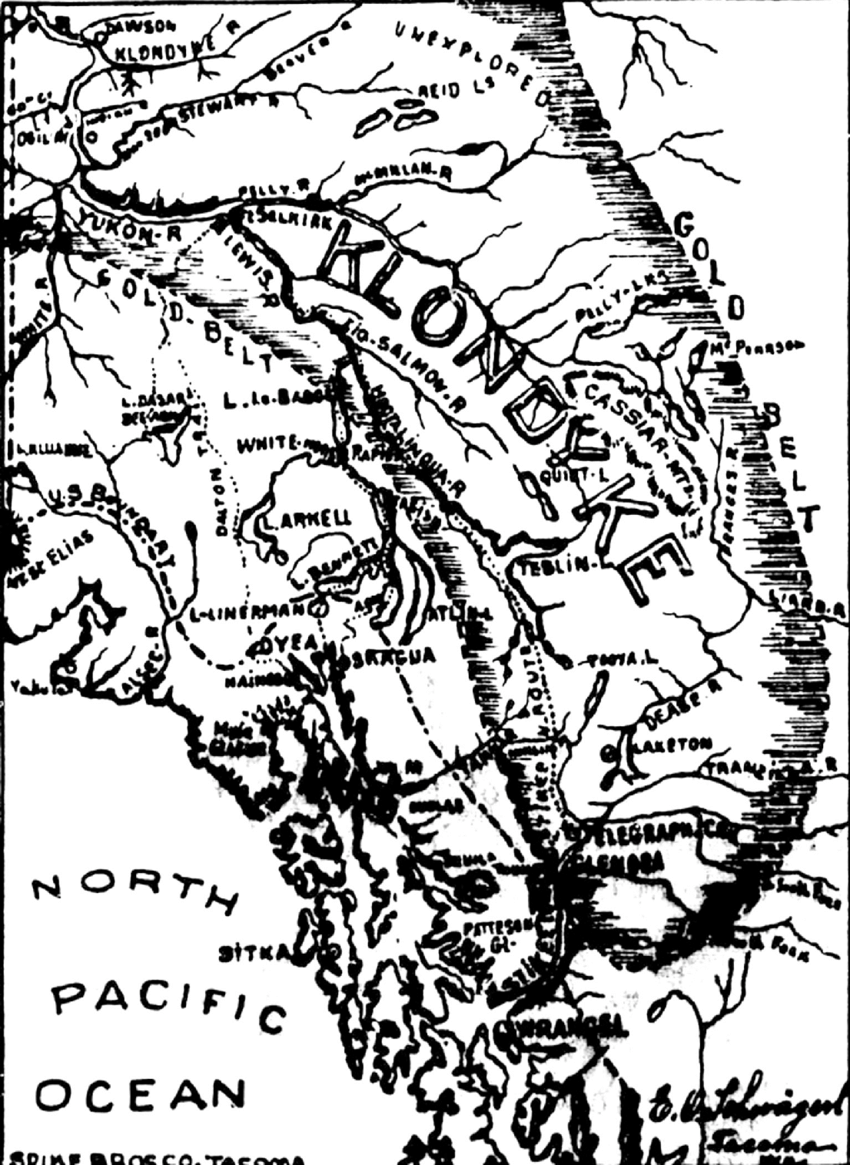

A 1898 booster map of the Teslin Trail/Stikine Route to the Klondike. Courtesy of Jonathan Peyton in his 2015 article, “A strange enough way: An embodied natural history of experience, animals and food on the Teslin Trail”

Writings nailed to trees along the way forewarn stampeders of this onerous trek, one such poem called “The Poor Man’s Trail” included the verse, “...this is the grave the poor man fills, after he died from fever and chills, caught while tramping the Stikine Hills, leaving his wife to pay the bills”. (Whig, 2016) Fortunately, neither Charles nor Lucille would meet their demise on this trail (though many others did) and by February had continued north into Tlingit territory where Lucille would give birth to her daughter. Upon learning the local name for the lake where they’ve stopped, Lucille says, “This is what I’ll call my daughter. For the lake where she was born. For you who have always lived here.” (Frontier Spirit, Duncan)

Photo of Teslin as an adult courtesy of Hidden Histories Society Yukon

The Hunters' rest was short lived and they continued on mere days after Lucille’s birth, heading north by dog team. Their tenacity having paid off, they beat thousands of stampeders to the punch and arrived in Dawson in the early spring of 1898, staking three claims at Bonanza Creek. Lucille worked through hard labour conditions alongside her husband, digging and prospecting while raising their daughter and running a restaurant. After WW I, the family expanded their mining ventures to Mayo, staking silver claims in the regions. For years as the family continued to mine the area, Lucille would regularly walk 225 km from Dawson to Mayo to ensure proper maintenance of the family’s claims. After Charles’ sudden death in 1939, Lucille would continue this work single-handedly. Post-WWII with the Alaska Highway under way (constructed in large part by African American soldiers) Lucille and her grandson, Buster moved to Whitehorse to open a laundry business. Despite progressively failing eyesight and a house fire, Lucille continued to live on her own throughout her time in Whitehorse. She was characterized as a “fiercely independent” woman, who was gracious and generous with her energy and space, continually entertaining guests until her death in 1972 at the ripe age of 94. Before her passing, Lucille was granted honorary membership by the Yukon Order of Pioneers because of her perseverance as a miner, making her not only the first female member, but also the first black member of the Order. Here’s to Lucille, heroic matriarch, black trailblazer, legendary badass.

Mrs. Lucille Hunter in her home, Whitehorse, 1960. (Yukon Archives, Richard Harrington fonds, #79-27 #277 PHO 014) (Courtesy of Hidden Histories of Yukon)

Aneke is a staff member at DWS.

Sources in Chronological Order

http://hhsy.org/wordpress/projects/hunter-family/

https://www.thewhig.com/2016/02/16/another-kind-of-white-person

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.ca/books/43716/frontier-spirit-by-jennifer-duncan/9780385659055

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/52057389/lucille-hunter

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/lucille-hunter-yukon-hidden-history-1.5907566